Presentation: MultiMimsy database extractions and the possibilities for OAI-based collections repositories at the Museum of London

UK MultiMimsy Users Group. Museum in Docklands, London, April 18, 2008.

Cultural heritage technologies, user experience design and research, digital humanities

UK MultiMimsy Users Group. Museum in Docklands, London, April 18, 2008.

These notes are taken from a panel presentation for the e-learning group held a 'Wine, Web 2.0 and What's New' event. The other panel members were Frankie Roberto (Science Museum), Mike Lowndes (ex-Natural History Museum) and Guy Grannum (National Archives).

Web 2.0 offers many exciting opportunities and you may feel under some pressure to 'go 2.0' and become fully buzzword-compliant. But wait! We shouldn't rush to replace existing systems or spend huge sums and many months on the latest technology buzzwords.

Instead, my contention is that a little Web 2.0 goes a long way, and is particularly useful when publishing niche content. Small scale projects can help expose your content to new audiences by making your content available for 'serendipitous discovery' or by making it accessible to potential but untapped audiences.

We can take advantage of low-cost, lightweight infrastructure/implementation nature of Web 2.0 applications to try small-scale online publishing projects. (As Frankie pointed out, make sure you take the time to inhabit Web 2.0 sites yourself first so you're familiar with the subtleties of how each site works).

For example, you can use Web 2.0 technologies to publish niche or specialist data that rarely gets funding for online publication (especially if it's not 'general' or schools audience-friendly) but is of great interest to, and a useful resource for specialist audiences.

Monitoring and evaluating the use of this data also allows specialists to make the case for further projects or better resources by demonstrating that there is public and peer interest in their objects, archive, collection or subject.

I'm going to briefly present two examples: Flickr, and addthis.

You can easily upload images from community projects or collections to Flickr, add appropriate metadata (titles, descriptions, labels), organise them into collections or sets, and geo-locate them by dragging them onto a map – all of which can enable the discovery of your collections by traditional or non-traditional, local or international audiences. It also makes your metadata available to search engines and can draw people back to your branded websites.

For instance, up to 70% of referrers on individual photos from the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre on Flickr are from external search engines. Generally the figure is around 20% (with the rest of the referrers being searches or browsing within Flickr), but it depends on the titles, descriptions and tags used.

Sites like Flickr don't replace a good content management system or collections database, but it can help you publish data that would otherwise never be seen.

For example, a small museum might use Flickr to publish object images and descriptions as a 'mini exhibition' or collection it couldn't otherwise afford to commission and host; or a department might put together a collection of their favourite items that are too fragile to display and link their Flickr page to blog posts about the objects and answer questions from visitors about the objects. We've used Flickr and blog software to publish a year-long research project about the glassworkers of Roman London for a whole new audience and for another 'behind the scenes' blog that is an experimental 'sneak peak into the working life of a museum'.

Sites like Flickr also provide easy ways to have visual 'conversations' with your visitors. The Dulwich Picture Gallery is a good example of the use of Flickr to build a community of visitors around event images.

Simple Web 2.0 applications or 'recommendation' services can help your audiences use your content in their 'real world' and share it with their friends and peers. You can take advantage of existing visitor habits online and follow the users' lead rather than blundering into their sites and committing a netiquette faux pas.

For example, addthis.com provides code that displays a button that you could put on your collections, events, research or venue information pages. When the visitor clicks the button, they can save the page to a shared or social bookmarking site like delicious or digg, share it on their Facebook page or blog it on their own site.

If you register for an account and put your username in the provided code, you can view reports that show which objects, events or information pages have been saved for reference or shared with others. This also provides an insight into which pages contain interesting or accessible content, which can in turn motivate internal content creators and help improve your online offerings.

The nice thing is that addthis do all the worrying about keeping up with the latest trends in social or participatory Web 2.0 sites for you as they adjust and update the button accordingly.

One important point you should always consider is your 'exit strategy' – is the data and the publication method future-proof? What if standards change? What if the company goes bust? Do you own your content? Can you get any user-generated content out? What if you invest in a site and it's suddenly no longer trendy? What if you're overrun by spam or the context around the content changes? However, you can generally mitigate these concerns if you address them at the start of the project and work through them.

In summary, Web 2.0 technologies allow you to be clever about how you give new life to existing content and offer your content the chance to be part of worldwide conversations.

An incomplete, retrospective list of work, talks and more in 2007…

I started to teach on a new Digital Humanities course in the Spring/Summer Term 2007 at Birkbeck. 'Introduction to Digital Humanities' was a new postgraduate course at Birkbeck College which combined aspects of media studies, humanities computing and literary studies to foster an appreciation of the core methods and practical, political/philosophical and pedagogical issues in digital humanities.

I devised and taught classes on:

I also gave a class on 'Computer assisted interpretation; integration of finds and site sequence' for the Birkbeck MA Archaeology Module "Archaeological Post-Excavation and Publication".

I gave a paper: Buzzword or benefit: The possibilities of Web 2.0 for the cultural heritage sector at the CAA (Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology) UK Chapter Meeting, January 24 – 26, 2007, Tudor Merchants Hall, Southampton

I gave what was possibly my first paper at an MCG conference, Sharing authorship and authority: user generated content and the cultural heritage sector (so web 2.0!) at Web Adept: UK Museums and the Web 2007, Leicester, June 22, 2007.

I started a blog for the Museum of London (so 2007) – 'first post', 'What does a database programmer do in a museum?'. A hilarious attempt to make my bio relatable: 'My job title is 'Database Developer', which means I am a specialised kind of computer programmer. I spend a lot of time working with the big databases that people like curators, collections managers, archaeologists and archivists use to record, analyse and publish their data. I talk to them to understand their requirements, then update or create applications to help them. I also help with geek stuff for the websites'. The blog didn't last, as so many didn't, but I still think 'About my museum job' posts were a great way to make museums more inclusive by showing all the different types of careers you could have in a museum.

I published a report: Nick Holder, Mia Ridge and Nathalie Cohen, The Tony Dyson Archive Project: Report of a pilot study investigating the creation of a digital archive of medieval property transactions along the City waterfront, Museum of London Archaeology Service. The linked file is a PDF version of the report, without mapping and plan diagrams.

I also contributed to the Çatalhöyük Archive Report 2007; an excerpt of my main bits is at https://doi.org/10.17613/3n8z-9z11. Blog posts on/from Çatalhöyük include:

Presentation for the Museums Computer Group's Web Adept: UK Museums and the Web 2007, Leicester, June 22, 2007.

Mia Ridge, Museum of London Group.

2007 Web Adept – UK Museums on the Web, Museums Computer Group conference

Summary: User-generated content complements and enhances institutional knowledge and authority while creating an engaging experience for the user. We can follow emerging best practices so that user-generated content is presented appropriately; but if user-generated content is still a challenge for museums, how should we move forward? This paper does not attempt to answer all of the questions about UGC in the cultural heritage sector but instead aims to name and problematise some of these issues and provide some pointers on what can be done so that we can begin to address them.

In this context user-generated content is defined as content produced by people outside cultural heritage organisations.

As you've seen in previous presentations, user-generated content is good for users and good for museums because users can help other users in ways that we don't have the resources to do. Some of the talks today should already have convinced you that UGC is beneficial for museums and the cultural heritage sector, particularly for its ability to promote our collections.

I'm sure by now you're familiar with the various types of UGC but just in case…

Deliberate or explicitly created UGC includes textual content such as forums (web applications where users can post messages on common topics or areas of interest), blogs (generally centrally authored content posted regularly in a format that allows users to comment), wikis (collaboratively created content), mailing lists (soooo ten years ago), and comments (free text responses to existing content such as blog posts or photos), tags and folksonomies.

It may also include polls or votes, photos, graphic images, videos, podcasts and relationships (whether between people on social networking sites or between objects 'favourited' or added to a personalised 'lightbox').

Implicitly generated UGC is not deliberately created, and is often revealed only through analysis of site logs, search terms and choices between results, and user paths. Relationships between items and clusters of tags can also be revealed through analysis. [This can be mined to create recommendations, or highlight items other visitors have found interesting.]

Users who create content in the cultural heritage sector include professional or amateur subject specialists; users who wish to share an emotional response or reminiscence about an object or topic; users who can contribute factual information or corrections about particular objects; users who create images, photos or fiction in response to cultural heritage content, (whether self-motivated or as part of a competition); and website visitors who create paths for others to follow by linking content through tags or paths through our sites. Users

also include peers from other museums or research institutions, including retired museum professionals.

User-created content often resides outside museum sites – if you search for your institution name or URLs within Flickr, Digg, YouTube or even Second Life you may be surprised at how much content people have already created about your institution. UGC can introduce us to audiences we didn't even know we have.

We're still learning about why users create content and what do they get out of it? And what are the risks for users?

There are a few different reports out there but one that's propagated quite widely is Jakob Neilsen's research which says that user participation often follows a 90-9-1 rule:

This creates the possibility that the requirements of the highly active and visible 1% of users are disproportionately represented. So what does this mean for museums and UGC? If resources are scarce, how much should be allocated to engaging with UGC? Do we design for the 90%, the 9% or the 1%? Are we focussing on some users at the expense of others?

More research is needed into participation models within our sector. In the meantime, we should address this by being sure to consult with or observe the silent majority when conducting user evaluation. Much as we balance the requirements of specialist and general users when designing projects, we must strike a balance between the requirements for supporting user-generated content and those of traditional publishing models.

The demonstrable return on investment has been covered in previous talks so we agree that UGC is valuable and enhances the experience of all users, then enabling the 1% and encouraging the 9% means that the 90% also benefit.

I've included examples from sites that you're probably familiar with to show how user-generated content can be integrated with trusted and authoritative content without compromising either source of content.

I think some of the big fears around UGC relate to trust and authority: how does UGC affect our users' trust in the authority of museum content? And how do museum staff react to UGC, and what are their particular fears? Perhaps they are generally comfortable with the idea of UGC as a thin layer of fluff above the reassuringly chunky content produced by a museum; but should UGC such as tagging be presented along museum taxonomies. Is there a role for UGC inside the museum or should it be kept separately?

Other questions: how do we deal with 'bad' UGC? Does the concept of 'incorrect' UGC vary according to the type of content? Does the 'halo effect' apply to 'bad' UGC on museum sites?

In answer, it seems that as long as the difference between UGC and museum authored content is clear, for example through the use of labels and careful presentation, users are able to differentiate between user-generated and museum content.

What models are there for creating trust in UGC? It is important to note that user-generated content is not written by random voices from an undifferentiated mass of users. Users can have identities and profiles. Most sites require users to create a login and published content is usually associated with a user name or user account.

E-commerce sites shows that reputation and trust are important, whether 'Real Name' reviewers on Amazon, established authors on Wikipedia, or eBay sellers with good feedback. Amazon reviews are a good example of a reputation system – other users can rate user-generated reviews and Amazon gives a special status to the Top 1000 Reviewers.

We need to understand when trust is important to our users so we can act accordingly. Trust is important when users are learning or will act on information, but may not be as important when reading about the experience of other users.

I haven't addressed the issue of radical trust today but obviously it's an issue to think about.

Building community may not always be part of the goals of a project but if it is, we should allow users to view content created by others along with information about those users, such as links to other content created by them, the number of items they have contributed and the length of time they've been involved with the site. Other possibilities include voting, rating, ranking or commenting on content generated by other users as well as direct interaction with other users. Consider partnerships with museums in the same geographical or specialist area to help build a critical mass of users. This also helps users who no longer have to understand which project or institutional 'silo' the content they seek is in.

The simplest method for differentiating between internally and externally authored content is labelling content by author. Presentation and design elements can also be used differentiate content sources/authors.

Always state the source of content and ideally state the date of content creation, the date last edited/updated and the source of the last change.

Don't mix product placement with museum or UGC. This will fundamentally shake user confidence in us as institutions that sit above market concerns. Keep external branding and sponsorship within well defined areas.

Web 2.0 and participatory web technologies mean that it's possible to start exploring UGC without massive budgets and timelines. You could ask for comments or user responses to rich object or information records online with a simple HTML form – this should be within the reach of even the most poorly resourced organisations. If you have object records online you could ask people to tag their photos or add them to a pool in Flickr link to the Flickr pages for those tags from the object or collection pages.

The requirements of our users should be at the heart of all our online offerings, whether or not we're incorporating UGC. It's important to understand what our users will want to do and how they'll interact with museum content when planning projects. If you are going to integrate UGC consider that the motivations and benefits for users creating content depends on the type of content they're creating. In theory we should all play a user advocate role through the project design and development process, but in practice consider nominating a 'user advocate' on each project – someone who asks, "how does this help the user?" at every stage.

Check whether you can actually fill a gap or whether those conversations already happening somewhere else – the market might be saturated with similar offerings. If that content doesn't exist elsewhere, are there existing models or infrastructure that you can re-use? Resources are scarce so re-invest in existing applications when possible. Re-using applications and existing conventions also provides benefits in user familiarity and ease of use. Make a decision about the levels of community and trust required and design user interactions and presentation accordingly.

Choose an appropriate moderation model and allow resources for moderation. Ideally UGC will be self-moderating, with review required only when inappropriate content is reported.

Decide how to respond to issues that arise through UGC. Define clear Terms of Service and enforce them consistently. Consider having a very short, plain language Welcome/Rules notice as well as a more in-depth Terms of Service.

Define and decide how to deal with inappropriate or controversial content and make that part of the Terms of Service. Also decide how to deal with negative feedback or criticism before it happens.

Decide how actively museum staff will be involved – will they just respond to requests for moderation, active encourage users to submit content (e.g. to photo pools on Flickr) or will they work with user groups to create new content in response to museum content?

Consider the accessibility of UGC. This can be intellectual accessibility as well as the usual accessibility issues such as visual impairment. It may be appropriate to provide tools for expanding acronyms and explaining jargon or provide guidelines for users creating content.

Make the scope of your project clear. Define your purpose, and follow it up with the design, information architecture and user interface elements – consistency counts. Think about the expectations you might be creating amongst your users and manage those expectations through clear statements of your capabilities and purpose. If you offer information services, tell users how soon you aim to respond, and if appropriate tell them how they can phrase questions for a best response.

Decide to what extent UGC will filter back into the museum and how that will be stored and presented. Also let users know how much control you'll give them over their user profiles and the information you hold about them.

Match the technology to the content. Points of analysis for each possible technology should include how much interaction it allows with other users (bear in mind that users will sometimes find ways of interacting even if you don't provide them! E.g. V&A tiles); how does it support community building; who are your audiences, why will they want to contribute; are those particular audiences already clustered around those technologies; what form will the UGC take (discrete responses to prompts in museum content, reminiscence, creative responses to suggested topics, sustained discussion on abstract topics, social networking, forums, comments, votes)?

Sustainability, re-usability and interoperability should also be considered. Ensure that any content created can be exported into an interoperable or portable format in case the application or supporting organisation fails, and take regular back-ups. Be aware that the publishers of APIs usually reserve the right to change their terms. Models of archiving for UGC are still developing, particularly on distributed services; so decide what suits your and your users' requirements.

Decide who owns the copyright for UGC for each project at the outside and provide a clear statement of copyright for each type of content on the site. Appropriate copyright clearance must be confirmed for object metadata, images and GIS data before publication. Provide a clear statement of how those rights apply across content used remotely via web services or in mash-ups.

Mash-ups aren't just technical – they can also combine different sources and fields of content to create radically new content.

You could publish a feed or API into your collections data or information records so that it can be used in mash-ups, or just make sure that your webpages are well-structured. Feeds of events information have an immediate application in social calendar sites like upcoming.org, online event listings.

Our visitors will 'push' content to their networks of friends and associates and market our content or us so make it easy for people to recommend or share your content: use stable URLs so that bookmarks always point to the same content. Be careful about how you use Flash/AJAX and don't use frames. Good use of page titles and HTML metadata also helps.

It's not up to us to reinvent technologies and create more information silos or social networks, but we should make it easy for people in social networks to engage with our content.

Scepticism about new fads is healthy but there are too many benefits for both our users and our institutions are too many to ignore the possibilities and challenges of UGC.

We can only prove the worth of UGC in the cultural heritage sector by working with it, and we can only address institutional fears about the ways in which UGC may offer to traditional authorship and authority by building UGC into our online offerings, one small step at a time.

[Was originally posted at Sharing authorship and authority: user generated content and the cultural heritage sector]

Presentation at Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology UK conference, January 24 – 26, 2007, Tudor Merchants Hall, Southampton

Mia Ridge, Museum of London

Computer Applications and Quantitative methods in Archaeology UK Chapter Meeting, January 2007

Yes, 'Web 2.0' is a buzzword, eagerly seized on by marketers and venture capitalists; but the technologies, methodologies and development philosophies it describes are of great potential benefit.

While "the participatory Web" might more accurately describe the benefits for cultural heritage organisations, 'Web 2.0' is a useful shorthand or umbrella term for a set of related ideas about how we develop for and use the web.

Wikipedia, a free encylcopedia written by volunteers and itself a Web 2.0 site, defines Web 2.0 as:

"Web 2.0, a phrase coined by O'Reilly Media in 2004, refers to a perceived or proposed second generation of Internet-based services—such as social networking sites, wikis, communication tools, and folksonomies—that emphasize online collaboration and sharing among users."

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2, January 2007

The following characteristics of Web 2.0 sites may be particularly relevant for archaeology:

O'Reilly presents the following examples for 'Web 1.0' and 'Web 2.0':

|

Web 1.0 |

Web 2.0 | |

|

DoubleClick |

–> |

Google AdSense |

|

Ofoto |

–> |

Flickr |

|

Akamai |

–> |

BitTorrent |

|

mp3.com |

–> |

Napster |

|

Britannica Online |

–> |

Wikipedia |

|

personal websites |

–> |

blogging |

|

evite |

–> |

upcoming.org and EVDB |

|

domain name speculation |

–> |

search engine optimization |

|

page views |

–> |

cost per click |

|

screen scraping |

–> |

web services |

|

publishing |

–> |

participation |

|

content management systems |

–> |

wikis |

|

directories (taxonomy) |

–> |

tagging ("folksonomy") |

|

stickiness |

–> |

syndication |

It may be almost provocative to present the above table, particularly as the reader may not agree with the labelling of all the examples.

'Web 2.0' sites include those that profit from an architecture of participation and user-generated content such as Amazon; those that use tagging or 'social bookmarking' to label content like photos or URLs such as Flickr, YouTube, last.fm, Del.icio.us or Digg; sites that use technologies such as syndication (particularly RSS) – for example, using a site such as Bloglines to track new additions to the Portable Antiquities Scheme's 'Finds of Note' service; podcasts and blogs; social network sites such as Myspace and Facebook; and sites that use application programming interfaces and web services such as Google maps mashups. Even pre-Web 2.0 sites that require audience participation like AmIHotorNot or Kitten War (where you are presented with images of two kittens and you 'vote' by clicking on the cuter photo) created the right environment for the participatory web to thrive. Radical trust, as seen in Wikipedia, is another Web 2.0-ish idea.

Concepts discussed in this paper include folksonomies and 'the long tail'. Folksonomies are defined as 'collaborative categorization schemes' or 'user generated taxonomies' (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folksonomy).

The theory of the Long Tail states "products that are in low demand or have low sales volume can collectively make up a market share that rivals or exceeds the relatively few current bestsellers and blockbusters" (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_tail). This has implications for organisations looking at the development and usage of online collections.

Only a few examples are presented today but increasingly cultural heritage organisations are publishing sites that use some 'Web 2.0' technologies or methodologies. When looking at other projects from within our sector it is important to ask, who is doing it well and what can we learn from them? How does the site meet the requirements of its audiences, and what can we learn from projects that did not quite work?

"Steve" is a collaborative research project exploring the potential for user-generated descriptions of works of art and while it is mostly used in American art museums, it provides a good model for the implementation of tagging and folksonomies in the heritage sector. Folksonomies can be important for cultural heritage organisations because "allowing users to describe collections—using their own vernacular or language – may help other users find things that interest them". This may improve access to and encourage engagement with cultural content.

As the project website says, "social tagging offers professional and volunteer staff insights into the ways that visitors experience objects in your collection. It enables museums to transcend traditional distinctions by department or medium so you can better serve your publics" (http://www.steve.museum/).

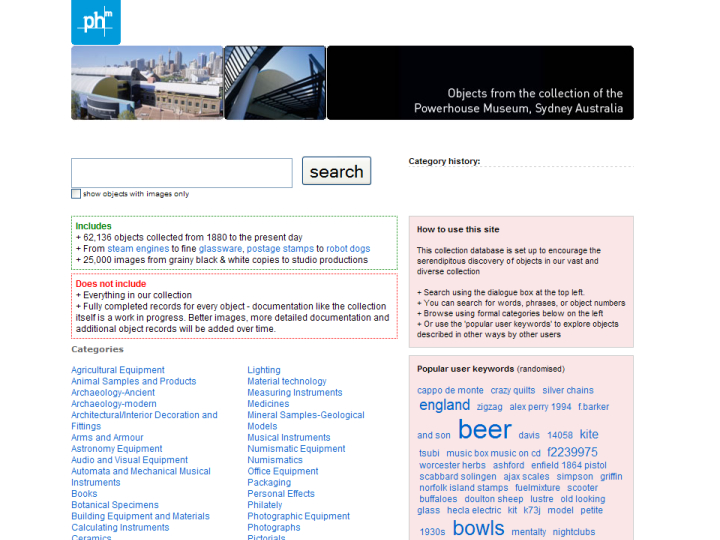

The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney re-launched their collection database online in June 2006.

Sebastian Chan from the Powerhouse Museum has a blog called 'Fresh + New' in which he talks about some of the work the Powerhouse is doing, including on-going tweaks to their OPAC 2.0 collection search.

In a post introducing their 'Collection 2.0' in June 2006 he said:

"Improving on previous collection search tools, OPAC 2.0 tracks and responds to user behaviour recommending 'similar' objects increase serendipitous discovery and encouraging browsing of our collection. It also keeps track of searches and dynamically ranks search results based on actual user interactions. Over time, this artificial intelligence will improve as it learns from users, and will allow for dynamic recommendations.

OPAC 2.0 also incorporates a folksonomy engine allowing users to tag objects for later recall by themselves or others. "

They have encouraged 'serendipitous discovery ' by implementing functionality such as the presentation of 'other search terms similar to X' and 'others who searched for X looked at' alongside search results as well as showing the tags other users have added so that 'almost every object view 'suggests' other objects to view'. This recommendation function is similar to Amazon's 'Customers who bought this item also bought'.

User-created tags are available as 'tag clouds', seen on the right-hand side of the screenshot, and are presented alongside the traditional museum-generated taxonomy.

The site has been a huge success. In August 2006 Chan posted:

"In just six weeks visitation to the Museum's website increased over 100%… In the 6 weeks from June 14-July 31 OPAC2.0 on its own received 239,001 visitors … who performed a total of 386,199 successful searches leading to object views … and over 1.2 million individual object views."

…

"The average number of successful searches per visit is 1.62.

The average number of objects viewed per visit is 5.02.

Contrast this with the single view per visit that objects on our previous 'packaged collection' received and the change is particularly marked."

At the 2006 National Digital Forum in New Zealand Chan reported that 95% of all available objects were visited at least once in the first ten weeks and that over 3,000 user tags had been added.

From the same post, this statement shows the effect of the long tail: "Now from our total object view figures we can determine that even the most popular object … represents only 0.1% of all views."

User-generated content and the 'participatory web' is a huge part of the success of Web 2.0. User-generated content (UGC) may be one of the biggest opportunities and one of the biggest challenges for heritage organisations.

For the purposes of this paper, user-generated content is considered as either 'implicitly generated' or 'explicitly generated' content. Implicitly generated UGC is created by the actions of users as they go about their normal business of viewing page, selecting search results or making purchases. This can be harnessed and used to generate things like general 'most viewed' lists or Amazon.com's 'people who bought this book also bought…' which is based on data generated by people with similar search and browsing patterns. The more a visitor uses Amazon and the more data they generate about their interests and preferences, the closer the matches get. Amazon 'Lists' and customer reviews are examples of explicitly generated content.

It is important to note that user-generated content is not written by random voices from an undifferentiated mass of users. Most sites require users to create a login and content is usually associated with a user name. Reputation and trust are important, whether 'Real Name' reviewers on Amazon, established authors on Wikipedia, or eBay sellers with good feedback. Amazon reviews are a good example of a reputation system – reviews can be rated by other users and Amazon gives a special status to the Top 1000 Reviewers.

Self-identifying and intentional users of cultural heritage websites include 'lifelong learners', subject specialists, potential clients (whether for archaeological work, or image or content licensing) and schools audiences. Other audiences include commercial contractors or clients and unintentional users who 'consume' our data via another interface entirely.

The benefits of the 'participatory Web' for both users and organisations go beyond greater visibility of cultural content and associated organisations – for example, specialist users may be able to add comments with information about parallels between objects in collection records held by different archaeological units or museums, or offer source references for more precise dating of objects. Web 2.0 technologies and practices may also help organisations engage with non-traditional audiences who encounter archaeological content in social network contexts or via web services.

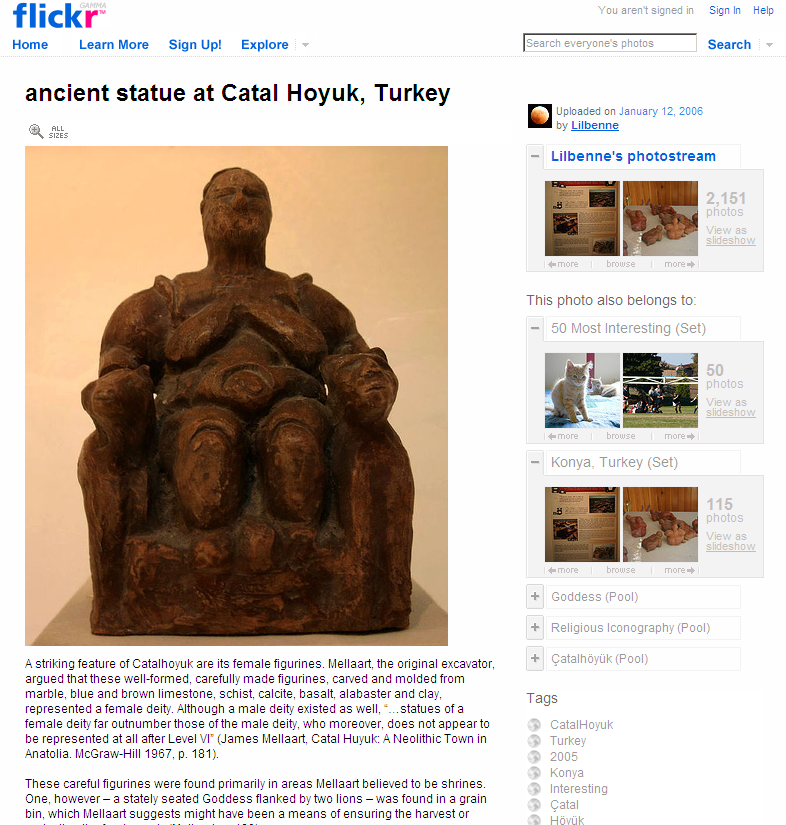

The Çatalhöyük project team have put excavation photos online at the photo-sharing site Flickr, and created a Flickr group for Çatalhöyük photos. Users can also search for photos geotagged in the area or tagged with relevant keywords (for example, http://flickr.com/photos/tags/catalhoyuk/). Some Flickr users have added a lot of text and tags to their photos, suggesting a high level of engagement with the material. Ideally, this user-generated content could be integrated more closely with the main site at http://www.catalhoyuk.com.

Visitors to the Çatalhöyük website can download raw data from the project database and produce their own interpretations but currently there aren't any methods for visitors to inform the project and other visitors about how they used the data and any interpretative or scientific conclusions reached. Web 2.0 technologies and methodologies might provide ideal solutions. For example, linking photos visible on Flickr with the online excavation and finds database could be a good way to encourage users to comment on and tag the photos and contribute their interpretation of the team's data.

Wessex Archaeology have recently implemented a project to integrate their web pages with photos hosted on Flickr and found usage increased greatly:

"Over the 12 months before September 2005, our gallery was viewed by an average of 480 people per month. 6 months after we began using Flickr, in March 2006, we received 5664 visitors (based upon sessions) to the FAlbum gallery script."

http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk/nwh/ART41987.html

How do the technologies and methodologies described as Web 2.0 apply to those working in archaeology or the cultural heritage sector? What can be picked from the hype and applied for the benefit of our organisations and our online audiences?

The specific benefits of Web 2.0 will depend on the goals of the organisation, but these may apply:

The Web 2.0 approach to standards-based presentation is advantageous for content producers and consumers. It encourages platform independence –

audiences may well be on mobile devices rather than a traditional PC. It is a chance to view creating attractive, innovative, accessible and standards-compliant sites as a challenge. Finally, standards compliance is increasingly a requirement for project funding from public bodies.

The use of open standards in application development and architecture is also beneficial. Many Web 2.0-ish applications are Open Source or run on Open Source platforms. One immediate benefit is that Open Source applications and platforms are free. Another is that they have years of development and testing with vociferous and demanding real world users behind them so they tend to be the robust and stable solutions.

The use of existing Web 2.0 infrastructures saves development costs. Audiences benefit from familiar interfaces and pre-existing logins, which may further encourage active engagement with 'cultural' content. Satisfied users will lead their social networks to your content, and create links and tags that will refer other users to the same service.

The use of Web 2.0 practices provides an impetus for organisations to think about the best licence under which to release content. Would they and their users benefit if content is released under a Creative Commons or Copyleft licence?

If data is to be published through a particular API or standard, the standard must be accessible to content creators and publishers as well as being realistically implementable. When there are competing standards, the choice between one and the other should be made carefully or deferred until a de facto standard emerges.

Some organisations will not have a dedicated IT department, or the technologies of Web 2.0 might not match the skillsets or training of existing staff. Some organisations do not have any control over their servers or architecture.

Organisations must be prepared for the possible challenge of corrections or re-interpretations from their audiences. Curators, archaeologists and other specialists are used to being the experts, disseminating their knowledge to the eager masses. How will they react to the idea of the masses writing back or expecting active engagement with the organisation? Further, are kids using organisations' pictures as the background to their Myspace page brats who are stealing bandwidth and intellectual property, or are they possibly members of a new generation of active and meaningfully engaged museum visitors?

The Terms of Use of partner sites should be reviewed in case they restrict the ability to re-publish content or content generated in response to original content.

Content may be placed in proximity with inappropriate or commercial content such as ads on commercial sites and the implications of this must be considered. Organisational branding might be affected by direct publication methods such as blogs.

Copyright clearance must be confirmed for object metadata, images and GIS data. Licensing requirements for software used, and client confidentiality should be considered.

Some existing social networking sites such as Myspace or Flickr tend to require active engagement and participation on the part of the institution or publisher to respond to audience engagement appropriately and get the full benefits of the site. This can have implications for the resources required to participate. In some cases it may not be appropriate for an organisation to comment on user-generated content and this must be considered.

Any user-generated content may require moderation and this has also resourcing implications. For example, at the Museum of London it has been noticed that every new collection site increases the number of curator enquiries. User forums and tagging may require on-going monitoring and moderation or the generation of new interpretation or research.

It is worth considering whether releasing content to distributed services will impact reported visitor numbers to traditional website or have an 'opportunity cost'. The usage of content released to web services may not be quantifiable.

Resistance may be encountered to the idea of committing resources to 'unproven' technologies. Mapping providers could disappear or start charging to use their web services or APIs, or change their licensing terms. Changes to the economic model might mean that existing services become unaffordable. Careful investigation can alleviate these concerns.

While there is research to be done on the best practices for Web 2.0 and the cultural heritage sector, the potential benefits for organisations and their audiences outweigh the risks and disadvantages. Organisations that develop Web 2.0-ish applications and data will contribute to the future understanding of the best ways to serve the diverse organisations and audiences in cultural heritage.

Ideally, organisations should consider why they want to take advantage of Web 2.0 technologies and practices, investigate the requirements of their audiences and consider the content available to them, then begin with small-scale projects then build on the response as appropriate. To quote the programming adage, "release early and often". Monitor usage and adjusting project requirements accordingly.

Suggestions for getting started include:

Organisations without dedicated IT resources may feel that Web 2.0 applications are out of their reach, but this does not have to be the case. Take advantage of existing models, particularly from commercial sites that have User Interface and Information Architect specialists – examine how Amazon separates user-generated content from 'official' content from publishers and authors, or how Flickr presents user comments compared to labels given by the content owner.

Match the technology to the content – you probably wouldn't publish your full finds catalogue as an RSS feed but if you regularly add small numbers of items a syndication or subscription model might be appropriate. Ensure that any content created can be exported into a interoperable or portable format in case the application or supporting organisation fails, and take regular back-ups. Investigate using open standards and Open Source Software where feasible, particularly where this avoids lock-in to proprietary systems.

Reduce moderation requirements by experimenting to set the right barriers to entry to suit specific audiences and content. Allow users to report offensive content for review by a moderator. Implement formal or informal peer review and reputation models to help the useful content rise and the non-useful content filter down. For example, tag clouds give prominence to the most popular tags while less popular tags become less visible; forum postings can be given 'karma' ratings by other visitors.

Consider using user-centred design methodologies, lightweight programming models and agile methods to reduce development time, therefore reducing the investment required. Take advantage of existing applications, services, APIs, architectures and design patterns wherever possible.

Finally, design for extensibility. Applications and infrastructure should be sustainable, interoperable and re-usable.

"Companies that succeed will create applications that learn from their users, using an architecture of participation to build a commanding advantage not just in the software interface, but in the richness of the shared data."

Tim O'Reilly, "What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software".

While the term 'Web 2.0' may just be more hype, the examples discussed have shown that there are real benefits to the technologies and methodologies described as 'Web 2.0'.

Chan, Sebastian. "Initial impacts of OPAC2.0 on Powerhouse Museum online visitation", https://web.archive.org/web/20081007233204/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/dmsblog/index.php/2006/08/10/initial-impacts-of-opac20-on-powerhouse-museum-online-visitation

Chan, Sebastian. "Opening the gates: new opportunities in online collections", http://ndf.natlib.govt.nz/about/forum2006-files/schan.pdf via http://ndf.natlib.govt.nz/about/projects.htm#_ndf2006

Chan, Sebastian. "Powerhouse Museum launches Web 2.0-styled collection search", https://web.archive.org/web/20080704143300/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/dmsblog/index.php/2006/06/08/powerhouse-museum-launches-web-20-styled-collection-search

Goskar, Tom. "Wessex Archaeology And Flickr: How We Use Web 2.0", http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk/nwh/ART41987.html

O'Reilly, Tim. "Web 2.0 Compact Definition: Trying Again", http://radar.oreilly.com/archives/2006/12/web_20_compact.html

O'Reilly, Tim. "What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software", http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, "Collection 2.0", https://web.archive.org/web/20180808113313/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database

Semantic Web Think Tank blog, "UK Museums and the Semantic Web; A not so formal ongoing commentary and discussion on the AHRC-funded thinktank", http://culturalsemanticweb.wordpress.com

Sierra, Kathy. "Why Web 2.0 is more than a buzzword", http://headrush.typepad.com/creating_passionate_users/2006/11/why_web_20_is_m.html

Wikipedia, Web 2.0, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2

http://www.amazon.co.uk/

https://web.archive.org/web/20141103060229/http://www.bloglines.com/

http://www.catalhoyuk.com/

https://web.archive.org/web/20210107062824/http://del.icio.us/

http://www.facebook.com/

http://www.faceparty.com/

http://www.finds.org.uk/

http://www.flickr.com/

http://www.hotornot.com/

http://www.kittenwar.com/

https://web.archive.org/web/20210109160935/https://myspace.com/

http://www.upcoming.org/

https://www.openobjects.org.uk/

[Originally posted at Buzzword or benefit: The possibilities of Web 2.0 for the cultural heritage sector]